Formalizing the Mathews Balancing Test

The 5th and 14th Amendments of the Constitution guarantee the federal and state governments, respectively, cannot deprive an individual of “life, liberty or property without due process of law.” In the landmark case of Mathews v. Eldridge (1976), the Supreme Court articulated three factors to weigh in determining whether the government had exercised due process when imposing such a deprivation. These three factors are:

“The private interest that will be affected by the official action,”

“[T]he risk of erroneous deprivation of such interest through the procedures used, and probable value, if any, of additional or substitute procedural safeguards,” and

“[T]he Government’s interest, including the function involved and the fiscal and administrative burdens that the additional or substitute procedural requirements would entail.”

This blog post will attempt to create a formula for determining the appropriate level of process required by Mathews. Such a formula, if adopted, would help reduce judicial error through the reduction of “noise.”

Why formalize Mathews?

It is fair to ask what purpose reducing the Mathews test to a formula serves. Aren’t lawyers notoriously bad a math? The primary benefit of formalizing the test is to reduce noise, which will necessarily reduce judges’ determining a given scenario requires too much or too little process.

“Noise” in this context refers to random variations in data that are not due to the underlying relationships being examined. Consider, for example, an IQ test. This test aims to measure intelligence, and, as a person’s intelligence does not change from day to day, it should return the same score each time a person takes the test within a reasonably short period of time. However, if one took several IQ tests, they would likely get a slightly different score each time. One reason for this difference would be confounding variables such as how well the test taker slept the night before, the time of day they took the test, what they did earlier in the day, etc. The IQ test is not aiming to measure how well the test-taker slept, but this variable nonetheless seeps into the data as “noise”, creating error.

A similar phenomenon likely takes place when a judge decides how much process is required under the Mathews test. Factors unrelated to the law unwittingly slip into her decision-making, leading her to grant more or less process than the law requires. Holding a judge’s bias constant, reducing noise should lead to a more accurate assessment of what process Mathews requires. In the below example, a judge consistently underestimates the amount of process Mathews requires (i.e. they are biased towards insufficient process). But even without addressing this bias, reducing noise will lead to more accurate decisions overall by eliminating large errors.

Though it is not obvious at first from this chart, the non-noisy but still biased blue judge assigned on average a level of process closer to that required by the law than the biased and noisy red judge — this is because the blue judge makes fewer large errors. In fact, reducing noise will reduce overall error just as much as reducing bias by the same amount will. For details on the statistical theory see the link in this footnote.1

Using a formula to determine the level of the process required by Mathews can help to reduce noise by providing a structured and systematic approach for analyzing the facts of any given case. The formula will help to ensure the judge considers all three factors and assigns a consistent weight to each factor for each decision. There is strong evidence mechanical formulas, as compared to "holistic" or "clinical" processes, reduce noise in decision-making.2

What is the best way to formalize Mathews?

To formalize Mathews, we will need to define dependent variables and independent variables.

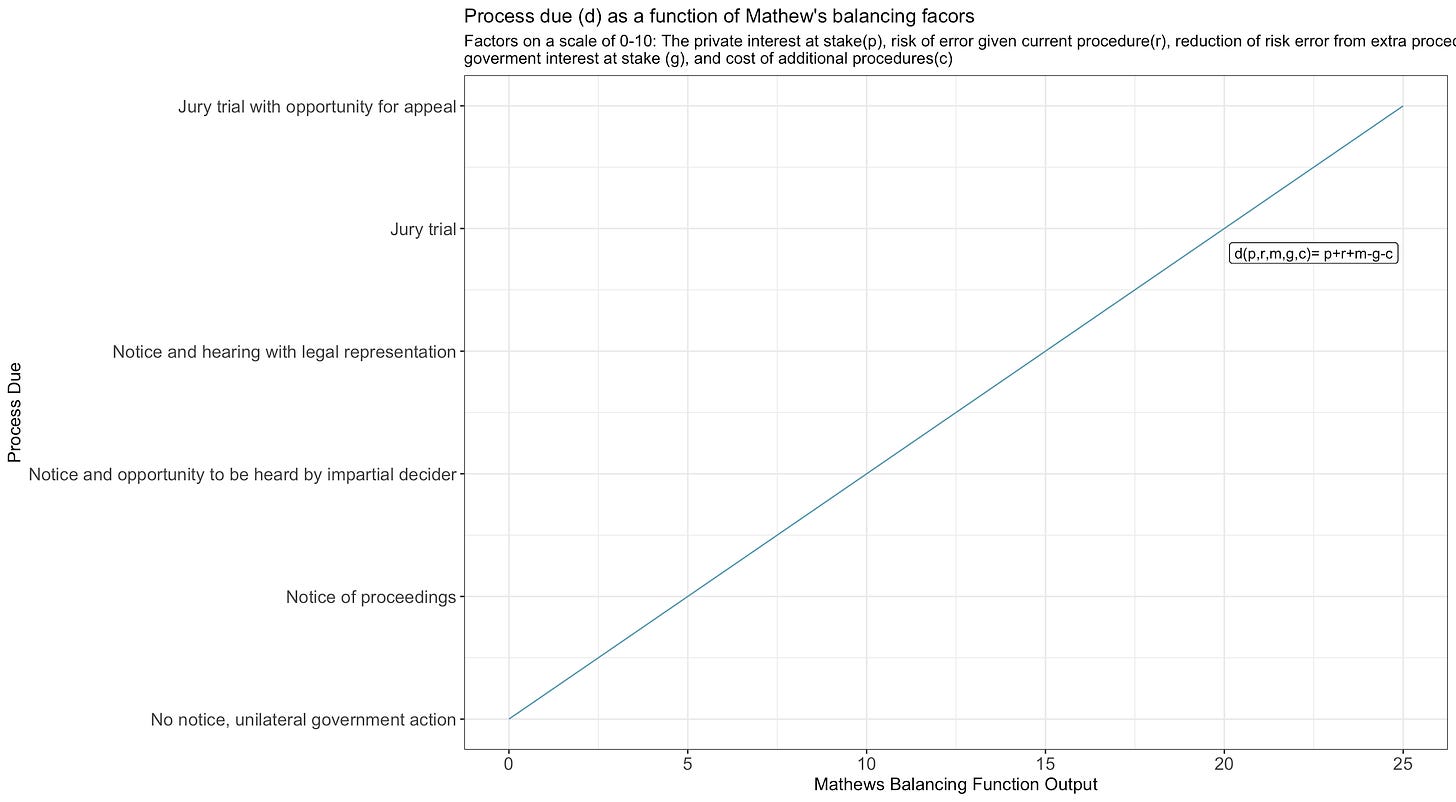

The dependent variable is the amount of process due. This dependent variable will sit on a sliding scale between 0 and 30, with 0 representing the least amount of process and 30 the most. We can then map various procesees onto these numerical values, as shown below.

0-4: No notice, unilateral government action

5-9: Notice of proceedings

10-14: Notice and opportunity to be heard by an impartial decider

15-19: Notice and hearing with legal representation

20-25: Jury Trial

25+: Jury trial with opportunity for appeal

The independent variables will be the three factors articulated by the court. Strictly speaking, the court combined two factors into one for the second and third factors, so we will have the five variables below:

The private interest that will be affected by the official action (‘p’)

The risk of erroneous deprivation of the private interest given the procedures used (‘r’)

The probable value of additional or substitute procedural safeguards (‘m’)

The Government’s interest in the current procedure (‘g’)

The fiscal and administrative burdens that the additional or substitute procedural requirements would entail (‘c’)

The straightforward and intuitive formula would be a simple linear model in which each of the independent variables is assigned a value between 0-10 based on the facts of the case, and the latter two variables are subtracted from the former three. Such a function would look like this:

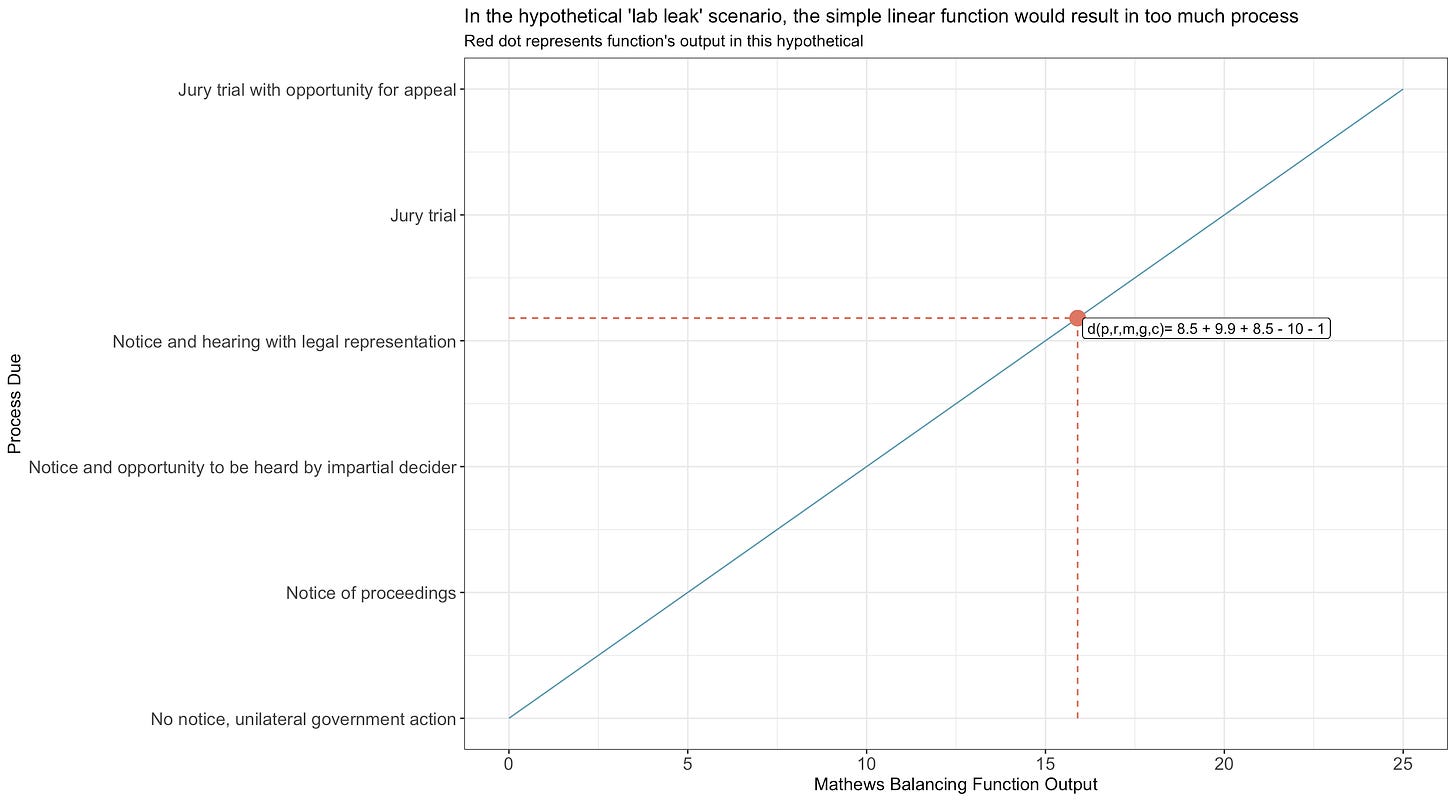

However, such a function runs into limitations when a strong government interest is in play. Suppose, for example, that the FBI had intercepted some communications between two people at a laboratory conducting virological research. These two individuals discussed detailed plans to imminently leak a virus that would be equally as transmissible and deadly as COVID-19. Suppose the FBI did not know which two individuals were communicating and 200 people worked at the lab and could potentially access the virus in question. Given the extreme government interest in avoiding another pandemic, it would seem obvious that the FBI could detain all 200 workers for until they could discover who the potential leakers were or secure the lab. However, under the linear formulation of the Mathews test, this would be a due process violation. The private interest, in this case, is high – with the detainees’ liberty being completely deprived for some non trivial amount of time. Further, the risk of error given the procedures is also very high — 99% — as 198 of the 200 detainees will have done nothing wrong. Adopting a different procedure such as only detaining individuals once some evidence was specifically tied to them would mitigate the risk of detaining any of the 198 innocent parties, and this additional process would not cost the government much because they would be conducting such an investigation in any event. The linear model then would look something like the below, and a notice and hearing with legal representation would be necessary prior to detaining anyone.

But it is unreasonable that the government would not be allowed to prevent a pandemic because of due process requires them to hold a hearing with legal representatives before detaining anyone. The model should be adjusted to allow for the government interest to extend as high as 30 to account for such edge cases. The lab leak hypothetical would look something like the below using this formula.

One potential objection to allowing the government interest to extend all the way to 30 is that it allows for a court to rule that no process is due any time they deem the government interest is strong enough, and that this power could be abused to strip citizens of their 5th and 14th amendment rights. However, courts already have this discretion, so formalizing the decision-making process does not make unconstitutional deprivations more likely.

See Kahneman, Sibony, and Sunstien’s Noise, pp. 57 https://ia804606.us.archive.org/11/items/ar_20211024/BOOKS.YOSSR.COM-Noise-A-Flaw-in-Human-Judgment.pdf

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/10752360/, https://psycnet.apa.org/record/2000-07311-003